Snakes, and reptiles in general, are so foreign to us. Their condition or status is often signaled by subtle behavioral cues, unlike the mammalian expressiveness of most of the animals we take into our homes. Yet they are often portrayed as “easy pets,” needing little attention or care.

After two snake-free years, again I find myself managing the care of two fine snakes, Rubber Boas this time. Small, secretive, and relatively slow as snakes go, these two are an entirely different experience. This morning, when I entered the study (where the Husband insists I keep them), they reminded me of the poem above. Two coils of boa were visible above the substrate in their cage. Like Nessie swimming in the loch, the small boa was porpoising along the bottom, neither head nor tail visible, swimming on waves of land. I had to watch closely even to tell which direction she was going.

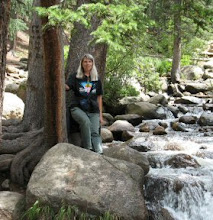

As she continued cruising, I decided to take her out to spend a few moments getting acquainted. It was cool in the room, and she coiled herself around my wrist for warmth, just as described at rubberboas.com She seemed content to sit quietly there for awhile, though perhaps disconcerted by the occasional swish through the air when I carefully moved my arm. It was awkward-- next time I’ll put her on the left arm so I can use the camera with my right.

As she continued cruising, I decided to take her out to spend a few moments getting acquainted. It was cool in the room, and she coiled herself around my wrist for warmth, just as described at rubberboas.com She seemed content to sit quietly there for awhile, though perhaps disconcerted by the occasional swish through the air when I carefully moved my arm. It was awkward-- next time I’ll put her on the left arm so I can use the camera with my right.

Speaking of heads and tails, as you can see, it’s hard to tell with these critters. Blunt tails and small heads are protective, an attempt to trick a predator into picking on the wrong end. The tail is also used to defend against the attacks of the mother mouse when they’re stealing babies from her nest for dinner. A result of these tactics is that the snakes, in the wild, are often heavily scarred. The larger of my two, who doesn’t like to come out much, has extensive scarring on her tail, but this one is almost unblemished.

No comments:

Post a Comment